Alexei Navalny leads Russians in a historic battle against arbitrary rule, with words echoing Catherine the Great

Women form a human chain on Feb. 14 in central Moscow to support jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny, his wife Yulia Navalnaya and other political prisoners.

Hilde Hoogenboom, Arizona State University

Tens of thousands of young Russians are protesting the leadership of Vladimir Putin nationwide in freezing temperatures. Thousands have been arrested.

Central to these well-organized protests is Russia’s opposition leader, Alexei Navalny. His courageous actions and words have inspired demonstrators to believe that they can change Russia.

As a scholar of Catherine the Great and the literature of Russia’s noble writers who served the empire, I pay attention to language.

Navalny uses some historically powerful words that speak to all Russians about the illegitimacy of their leaders and government.

A normal country

A lawyer, Navalny became a prominent regime critic a decade ago, when he created the Anti-Corruption Foundation and ran for mayor of Moscow. Funded by Russian donors, his national foundation collects stories of government corruption and produces YouTube videos that document, with drone footage, the secret luxury properties of government officials.

https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=400&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=400&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=503&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=503&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=503&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px">

https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=400&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=400&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=503&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=503&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385851/original/file-20210223-23-wtumw6.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=503&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px">

Sefa Karacan/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Navalny is not a Moscow flash in the pan. Members of his team have built a presence in about 50 cities using their political party, Russia of the Future. He has suffered multiple arrests, convictions and physical attacks.

Navalny’s “smart” voting platform recommended that candidates unite opposition votes last year against Putin’s United Russia party, which lost seats in Moscow, Khabarovsk, Tomsk and Novosibirsk. Putin’s party faces further losses and delegitimization in parliamentary elections in September.

Last summer, Navalny was poisoned in an apparent assassination attempt, and the Russian government allowed him to be evacuated to a German hospital, where he recovered. One of his YouTube videos featured what he said was a member of the Kremlin’s security agency, the FSB, confessing that the agency poisoned Navalny. Supporters live-streamed his return to Moscow and arrest on Jan. 17.

Sentenced to nearly three years in prison on Jan. 22, Navalny made a courtroom speech that mocked the “performance” of justice.

“This is what happens when lawlessness and arbitrary power become the essence of a political system, and it is horrifying,” he said. “But it is even worse when lawlessness and arbitrary power pose as state prosecutors and dress up in judges’ robes. It is the duty of every person not to submit to you or such laws.”

Interrupted by the judge, Navalny repeated these sentences.

In that statement, Navalny used the term “proizvol,” a word that means arbitrary power, and is often translated as tyranny. Russians have used this word for centuries to describe the abuse of power at all levels of government and society. Like Soviet dissidents before him, Navalny is demanding that the government uphold its own laws.

Navalny concluded with a call for “normal justice, normal relations, participation in elections, participation in the distribution of national wealth.”

Navalny echoes Russians’ historical wish: to live in a normal European country governed by the rule of law. Empress Catherine the Great – a German – first expressed this enlightened goal in her “Instruction” to her Legislative Commission as it began to review Russia’s laws in 1767: “Russia is a European nation.”

Civil society

Navalny’s ideas, his YouTube channel, his foundation and his political party embody one of the most powerful political concepts to arise in the past few decades.

Since the 1990s, philosophers such as Michael Walzer have revived the notion of “civil society” to empower citizen democracy in Eastern Europe and Russia. In this approach to society, nongovernmental organizations such as churches, clubs, unions, neighborhoods, foundations and political parties bring people together. They create civic networks that can check the power of government and promote the greater good.

These nonprofit organizations and advocacy groups in Russia were initially funded in the 1990s by the United States, the European Union and the philanthropist George Soros. Putin branded these organizations as foreign agents after massive demonstrations against his reelection in 2012 amid reports of election fraud by independent Russian election monitors.

Western notions of civil society resonated in Russia because civic duty has been essential to Russian culture for centuries.

https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=535&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=535&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=673&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=673&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=673&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px">

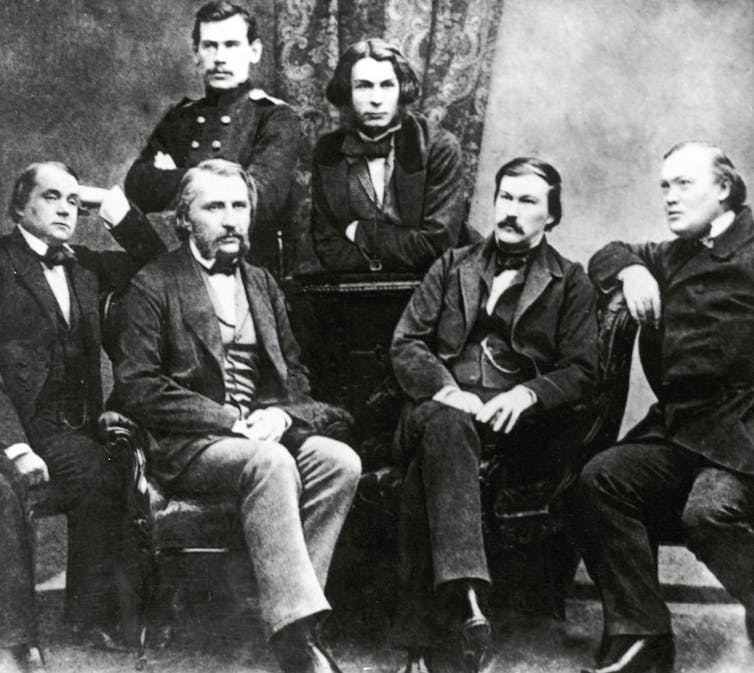

https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=535&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=535&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=673&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=673&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/385903/original/file-20210223-14-1ygzbuh.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=673&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px">Duty to the public good was the lifeblood of the Russian nobility – and authors like Tolstoy, top left, and Turgenev, second from left on bottom row, exemplified that ideal in their novels, which are studied by Russian students today.

Imagno/Hulton Archive via Getty Images

In 1767, during the Scottish Enlightenment, Adam Ferguson published “An Essay on the History of Civil Society” to promote an idea going back to the Greeks. Ferguson wrote that in a civil society, the social, political and military elites had a civic duty to the greater common good. His great fear was that elites were too corrupted by privilege to do their duty.

Nineteenth-century philosophers such as Hegel recast Ferguson’s work and transmitted their ideas to the Russian intelligentsia. The notion of a duty to the public good was the lifeblood of the Russian nobility, who were compelled to serve in the military or civil service and ran the Russian empire.

A post-Putin Russia?

Nobles like the writers Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Turgenev exemplified those civic ideals in their novels - the novels that students in Russia read today to pass their Unified State Exams. Brought up on new and old notions of civil society, young people understand when Navalny says that his movement is not about him, but about them and their future.

The Russian government playbook has been to exile major dissidents abroad and delegitimize them].

But Navalny heroically returned to his country after the government’s assassination attempt, even knowing that he faced certain arrest and prison, and possibly death. His team has used his palpable bravery to mobilize demonstrators in some 150 cities throughout Russia.

The demonstrators were equally motivated by Navalny’s release, two days after his return, of the bombshell two-hour video “A Palace for Putin: The History of the Largest Bribe.” It documents Putin’s decades-old network of elite bagmen, his expensive mistresses and his luxury tastes for US$850 Italian gilded toilet brushes – which became a new protest symbol. An existential challenge to Putin’s legitimacy, the video has over 110 million views.

As Russians prepare for parliamentary elections in September, they sense that historic change may once again be possible – with the potential for a more democratic future.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]![]()

Hilde Hoogenboom, Associate Professor of Russian, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Latest from The Conversation

- Outside Supreme Court justice’s home, a Revolution-era flag, now a call for Christian nationalism

- How ‘La Catrina’ became the iconic symbol of Day of the Dead

- A reflexive act of military revenge burdened the US − and may do the same for Israel

- Beer and spirits have more detrimental effects on the waistline and on cardiovascular disease risk than red or white wine

- Legalizing recreational pot may have spurred economic activity in first 4 states to do so