Twitter posts show that people are profoundly sad – and are visiting parks to cheer up

- Written by The Conversation

- 0 comments

Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty Images

Central Park, New York City, on Memorial Day weekend, May 24, 2020.

Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty Images

Central Park, New York City, on Memorial Day weekend, May 24, 2020.

Joe Roman, University of Vermont and Taylor Ricketts, University of Vermont

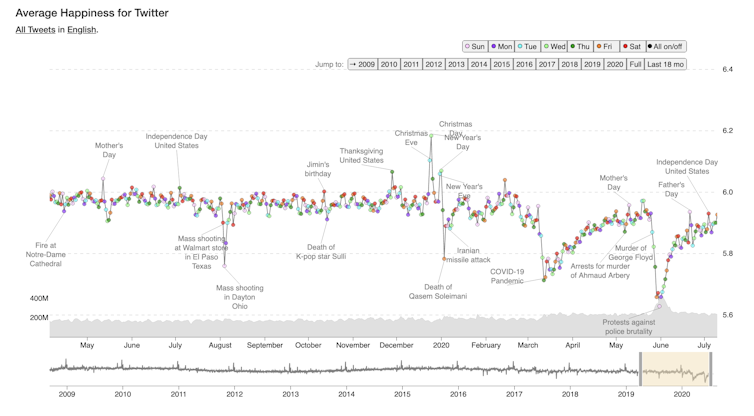

The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is the deepest and longest period of malaise in a dozen years. Our colleagues at the University of Vermont have concluded this by analyzing posts on Twitter. The Vermont Complex Systems Center studies 50 million tweets a day, scoring the “happiness” of people’s words to monitor the national mood. That mood today is at its lowest point since 2008 when they started this project.

They call the tweet analysis the Hedonometer. It relies on surveys of thousands of people who rate words indicating happiness. “Laughter” gets an 8.50 while “jail” gets a 1.76. They use these scores to measure the mood of Twitter traffic.

https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=331&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=331&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=416&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=416&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=416&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px">

https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=331&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=331&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=416&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=416&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/348999/original/file-20200722-26-1u7hs0l.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=416&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px">The Hedonometer measures happiness through analysis of key words on Twitter, which is now used by one in five Americans. This chart covers 18 months from early 2019 to July 2020, showing major dips in 2020.

hedonometer.org

These same tweets also indicate a potential salve. Before pandemic lockdowns began, doctoral student Aaron Schwartz compared tweets before, during, and after visits to 150 parks, playgrounds and plazas in San Francisco. He found that park visits corresponded with a spike in happiness, followed by an afterglow lasting up to four hours.

Tweets from parks contained fewer negative words such as “no,” “not” and “can’t,” and fewer first-person pronouns like “I” and “me.” It seems that nature makes people more positive and less self-obsessed.

Parks keep people happy in times of global crisis, economic shutdown and public anger. Research has also shown that transmission rates for COVID-19 are much lower outdoors than inside. As scholars who study conservation and how nature contributes to human well-being, we see opening up parks and creating new ones as a straightforward remedy for Americans’ current blues.

Park visits are up during the pandemic

According to the Hedonometer, sentiments expressed online started trending lower in mid-March as the impacts of the pandemic became clear. As lockdowns continued, they registered the lowest sentiment scores on record. Then in late May, effects from George Floyd’s death in police custody and the following protests and police response once again could be seen on Twitter. May 31, 2020 was the saddest day of the project.

Recent surveys of park visitors around the University of Vermont have shown people using green spaces more since COVID-19 lockdowns began. Many people reported that parks were highly important to their well-being during the pandemic.

The powerful effects of nature are strongest in large parks with more trees, but smaller neighborhood parks also provide a significant boost. Their impact on happiness is real, measurable and lasting.

Twitter records show that parks increase happiness to a level similar to the bounce at Christmas, which typically is the happiest day of the year. Schwartz has since expanded his Twitter study to the 25 largest cities in the U.S. and found this bounce everywhere.

Parks and public spaces won’t cure COVID-19 or stop police brutality, but they are far more than playgrounds. There is growing evidence that parks contribute to mental and physical health in a range of communities.

In a 2015 study, for example, Stanford researchers sent people out for one of two walks: through a local park or on a busy street. Those who walked in nature showed improved moods and better memory performance compared to the urban group. And a team led by Gina South of the University of Pennsylvania showed in a 2018 study that greening and cleaning up blighted vacant lots in Philadelphia reduced local residents’ feelings of depression, worthlessness and poor mental health.

Creative strategies

It isn’t easy to create new parks on the scale of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park or the Washington Mall, but smaller projects can expand outdoor space. Options include greening vacant lots, closing streets and investing in existing parks to make them safer, greener and shadier and support wildlife.

These initiatives don’t have to be capital-intensive. In the University of Pennsylvania study, for example, renovating a vacant lot by removing trash, planting grass and trees and installing a low fence cost only about US$1,600.

https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=450&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=450&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=566&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=566&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=566&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px">

https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=450&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=450&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=566&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=566&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/351170/original/file-20200804-14-1qshxh4.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=566&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px">Waterfall Garden Park, a pocket park in Seattle built and maintained by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Joe Mabel/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

Urban green space is most needed in neighborhoods that have lacked funding for parks, especially given COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on Black and Latinx people.

Cities can also create parklike spaces by closing streets to cars. Many cities worldwide are currently retooling their transportation systems for the post-COVID-19 world in order to reallocate public space, widen sidewalks and make more space for nature.

Urban designers, artists, ecologists and other citizens can play a direct role, too, creating pop-up parks and green spaces. Some advocates transform parking spaces into mini-parks with grass, potted trees and seating for just the time on the meter, to make a larger point about turning so much public space over to cars.

Or cities can invest a little more. Minneapolis, Cincinnati and Arlington, Virginia, have won national recognition for their ambitious investments in public park systems. These areas could serve as models for neighborhoods that lack access to parks.

A New Park Deal?

The United States has historically driven economic recovery with major infrastructure investments, like the New Deal in the 1930s and the 2009 American Reinvestment and Recovery Act. Such investments could easily include nature-positive spaces.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Parks are not panaceas, as evidenced by the widely publicized racist confrontation between a white woman and a Black birder in New York’s Central Park in early July. But Hedonometer data add to a growing body of evidence that they provide clear mental health benefits. Creating and expanding parks also generates jobs and economic activity, with much of the money spent locally.

We believe investments in nature are well worth it, offering both short-term solace in difficult times and long-term benefits to health, economies and communities.![]()

Joe Roman, Fellow, Gund Institute for Environment, University of Vermont and Taylor Ricketts, Professor and Director, Gund Institute for Environment, University of Vermont

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.